Story

mai 14, 2016

Text Maren Serine Andersen Photos Luca Sorheim

My aunt wrote and asked me if I wanted to go to an art exhibition. She was traveling from the south-west coast this weekend to spend some time in Oslo, and we had already planned to get together. I got curious immediately and asked her which exhibition she had in mind. She wanted to go to the Astrup Fearnley Museum, and the idea thrilled me right away knowing that this would be last day of the exhibition Bildungsroman by Mathew Barney and said yes.

At first I had been totally unaware of Mathew Barney’s ability of magnifying ideas and objects out of proportion, and the massive amount of details in his works transforming his imagination to materialize in reality. After the day that Ida Moen from the Astrup Fearnley Museum introduced the Contemporary Art superstar’s complex universe to me, I had been at the exhibition twice and seen two of Mathew Barney’s films. In the beginning I just admired his sculptures as beautiful objects, but as I started to recognize them as props in the films that were looped on juxtaposed screens, I started to get a bit frightened by the gloomy vibes that changed the sculptures.

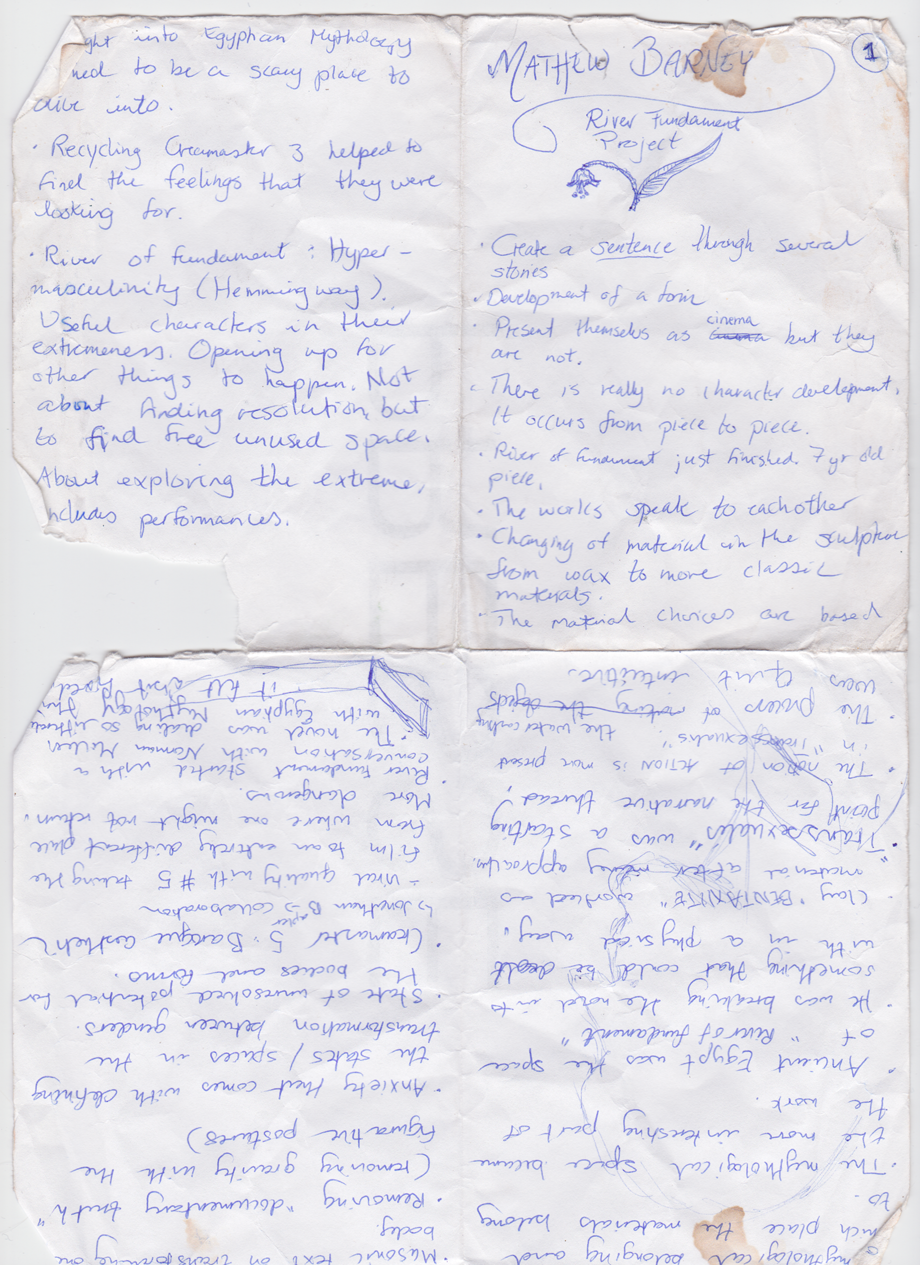

When Mathew Barney visited the Museum for a conversation about his artistic body of work with the critic and curator Catherine Taft, I knew almost nothing about him and hadn’t even seen a picture of the man. My first impression was how calm he seemed when he entered the room that was absolutely packed with audience. My second impression was that he looked casually underdressed but also noticed that his shoes looked very expensive. The way he talked about his ideas around creative process felt almost like hearing about a new kind of science as the precision and intricate details of his projects were overwhelming with advanced information.

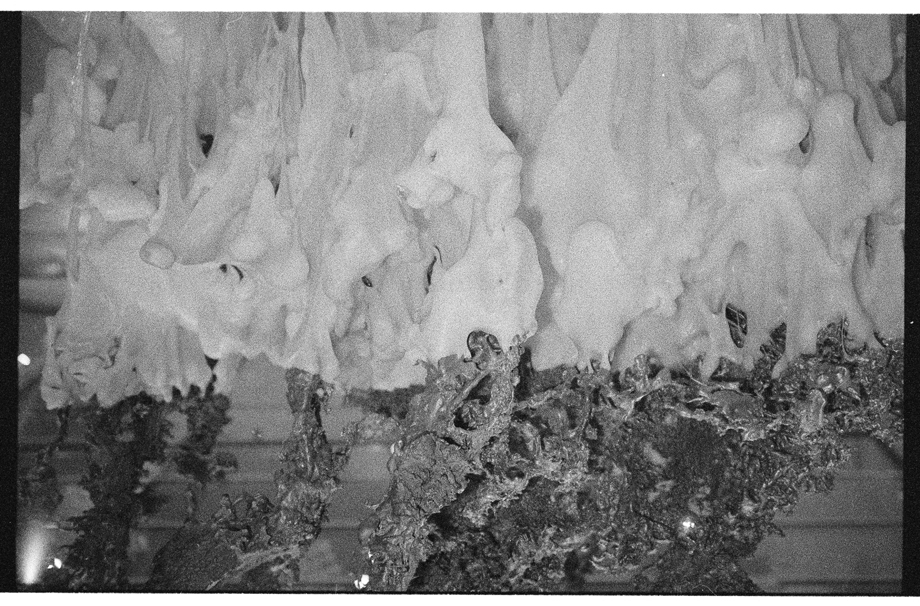

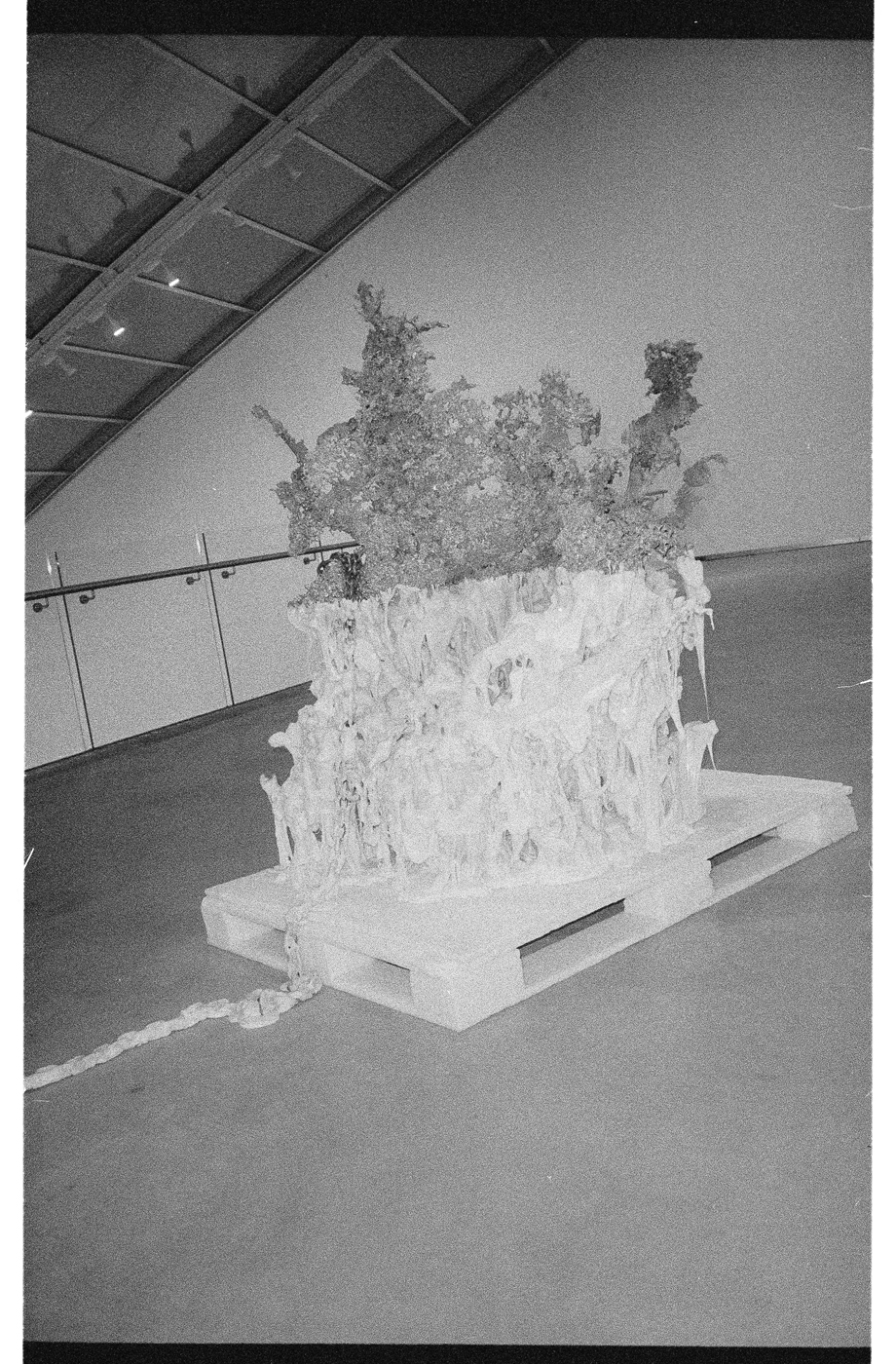

According to Gunnar B. Kvaran, director of the Astrup Fearnley Museum, Mathew Barney is definitely the artist from the 1990’s that has changed the tradition of sculpture most thoroughly. The exhibition «Bildungsroman» collects Barney’s legendary sculptures from the 1990’s, like Transexualis (decline) with newer pieces, like the amazing White Dwarf. The most central symbol in Mathew Barney’s universe is the field emblem, a capsule bisected by a horizontal line, which appears in many of his films. Because of its symmetry, it is used as a symbol for a state of equilibrium. At times, a “half field emblem” represents a state where one option has gained dominance. The field emblem can also be read as a symbol of an orifice in both its open state as a capsule and closed state as a line. The symbol is part of the sculpture Transexualis (decline), and it also appears as an enormous independent sculpture on the deck of a boat in his film collaboration Drawing Restraint that he created together with ex-girlfriend and fellow artist Björk.

White Dwarf

I was reading my notes on their film collaboration and remembered Bjørk’s beautiful red cape and her hot Yuzu bath scene when someone that I hadn’t talked to for a while suddenly wrote to me. I did get a little annoyed letting myself be so easily distracted, but wrote him back right away. All I focused on at that point were beautiful images anyway, and it felt impossible to find an essence of Mathew Barney’s work.

When I told him that I was working on a text about Mathew Barney, my friend offered me his original Cremaster book from the nineties, and pointed out that the weight of it was at least 10 kilograms. Uncertain of wether this was just a clever insult or if I was actually offered a gift, I replied to him on impulse how perfect the heavy book would be for squats. Shortly after it occurred to me that my fantasy of using the book to exercise was actually a natural reference to some of the elements that dominated my idea of Mathew Barney’s artistry: symbolism, resistance and mixing arts with athletics. Besides that this was absolutely an experimental use of material, something he is famous for.

In his universe, the spectator is moving through a detailed combination of sculpture, installation and performance put together. Even though the sculptures are impressive pieces of work, these are only fragments of Mathew Barney’s complex artistry. Being infatuated with his beautiful objects at first sight is not hard. One reason for this might be his inability to follow any one particular thread to the end. The artist personally thinks that part of this is not wanting to understand something completely to the point where the project will become about that thing. He thinks this is the way that he absorbs things on a day-to-day way and that there isn’t necessarily a conscious. What is most exciting to him is when his ego dissipates and the project becomes much larger than he is, and it starts to make its own demands.